《神奇4俠:英雄第一步》視覺特效製作解析,數字王國的突破時刻 / 閱讀全文

2025年09月09日

Featured in VFX Voice

Getting a reboot is the franchise where an encounter with cosmic radiation causes four astronauts to gain the ability to stretch, be invisible, self-ignite and get transformed into a rock being. Set in a retro-futuristic 1960s, The Fantastic Four: First Steps was directed by Matt Shakman and features the visual effects expertise of Scott Stokdyk, along with a significant contribution of 400 shots by Digital Domain, which managed the character development and animation of the Thing (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), Baby Franklin, Sue Storm/Invisible Woman (Vanessa Kirby), Johnny Storm/Human Torch (Joseph Quinn) and H.E.R.B.I.E. (voiced by Mathew Wood). At the center of the work was the in-house facial capture system known as Masquerade 3, which was upgraded to handle markerless capture, process hours of data overnight and share that data with other vendors.

“We were brought on early to identify the Thing and how to best tackle that,” states Jan Philip Cramer, Visual Effects Supervisor at Digital Domain. “We tested a bunch of different options for Scott Stokdyk and ended up talking to all of the vendors. It was important to utilize something that everybody can use. We proposed Masquerade and to use a markerless system, which was the first step for us to see if it was going to work, and are we going to be able to provide data to everybody? This was something we had never done before, and in the industry, it’s not common to have these facial systems shared.”

Digital Domain, Framestore, ILM and Sony Pictures Imageworks were the main vendors. “All the visual effects supervisors would get together while we were designing the Thing and later to figure out the FACS shapes and base package that everybody can live with,” Cramer explains. “I was tasked with that, so I met with each vendor separately. Our idea was to solve everything to the same sets of shapes and these shapes would be provided to everybody. This will provide the base level to get the Thing going, and because so many shots had to be worked on in parallel, it would bring some continuity to the character. On top of that, they were hopeful that we could do the same for The Third Floor, where they got the full FACS face with a complete solve on a per-shot level.”

Continues Cramer, “A great thing about Masquerade is that we could batch-solve overnight everything captured the previous day. We would get a folder delivered to us that would get processed blindly and then the next morning we would spot-check ranges of that. It was so much that you can’t even check it in a reasonable way because they would shoot hours every day. My initial concern of sending blindly-solved stuff to other vendors was it might not be good enough or there would be inconsistencies from shot to shot, such as different lighting conditions on the face. We had to boil it down to the essence. It was good that we started with the Thing because it’s an abstraction of the actor. It’s not a one-to-one, like with She-Hulk or Thanos. The rock face is quite different from Ebon Moss-Bachrach. That enabled us to push the system to see if it worked for the various vendors. We then ended up doing the Silver Surfer and Galactus as well, even though Digital Domain didn’t have a single shot. We would process face data of these actors and supplied the FACS shapes to ILM, Framestore and Sony Pictures Imageworks.”

Another factor that had to be taken into consideration was not using facial markers. We shot everything markerless and then the additional photography came about,” Cramer recalls. “Ebon had a beard because he’s on the TV show The Bear. We needed a solution that would work with a random amount of facial hair, and we were able to accommodate this with the system. It worked without having to re-train.” A certain rock was chosen by Matt Shakman for the Thing. “Normally, they bring the balls and charts, but we always had this rock, so everybody understood what the color of this orange was in that lighting condition. That helped a huge amount. Then, we had this prosthetic guy walking through in the costume; that didn’t help so much for the rock. On the facial side, we initially wanted to simulate all the rocks on the skin, but due to the sheer volume, that wasn’t the solution. During the shape-crafting period, there was a simulation to ensure that every rock was separated properly and were baked down to FACS shapes that had a lot of correctives in them; that also became the base FACS shape list for the other vendors to integrate into their own system.”

There were was a lot of per-shot tweaking to make sure that cracks between the rocks on the face of the Thing were not distracting. “It was hard to maintain something like the nasolabial folds [smile lines], but we would normally try to specifically angle and rotate the rocks so you would still get desired lines coming through, and we would have shadow enhancements in those areas as well,” Cramer remarks. “We would drive that with masks on the face.” Rigidity had to be balanced with bendability to properly convey emotion. “Initially, we had two long rocks along the jawline. We would break those to make sure they stayed straight. In our facial rig we would ensure that the rocks didn’t bend too much. The rocks had a threshold for how much they could deform. Any rock that you notice that still has a bend to it, we would stiffen that up.” The cracks were more of blessing than a curse. Cramer explains, “By modulating the cracks, you could redefine it. It forced a lot of per-shot tweaks that are more specific to a lighting condition. The problem was that any shot would generate a random number of issues regarding how the face reads. The first time you put it through lighting versus animation, the difference was quite a bit. In the end, this became part of the Thing language. Right away, when you would go into lighting, you would reduce contrast and focus everything on the main performance, then do little tweaks to the rocks on the in-shot model to get the expression to come through better.”

A family member was recruited as reference for Baby Franklin. “I had a baby two and a half years ago,” Cramer reveals. “When we were at the beginning stages of planning The Fantastic Four, we realized that they needed a baby to test with, and my baby was exactly in the age range we were looking for. This was a year before the official production started. We went to Digital Domain in Los Angeles and with Matt Shakman shot some test scenes with my wife there and my son. We went to ICT [USC Institute for Creative Technologies], and he was the youngest kid ever to be scanned by them. We did some initial tests with my son to see how to best tackle a baby. They would have a lot of standard babies to swap out, so we needed to a bring consistency to that in some form. Obviously, the main baby does the most of the hero performances, but there would be many others. This was step one. For step two, I went to London to meet with production and became in charge of the baby unit they had. There were 14 different babies, and we whittled it down to two babies who were scanned for two weeks. Then we picked one baby deemed to be the cutest and had the best data. That’s what we went into the shoot with.”

Not every Baby Franklin shot belonged to Digital Domain. “We did everything once the Fantastic Four arrive on Earth and Sue is carrying the baby,” Cramer states. “When you see it now, the baby fits in my hand, but on set, the baby had limbs hanging down both sides because of being double the scale of what’s in the film. In those cases, we would use a CG blanket and paint out the limbs, replace the head and shrink the whole body down. It was often a per-shot problem.” The highest priority to make sure that the baby can only do what it’s supposed to do. “Matt Shakman had an amazing idea. He had Sue, or the stand-in version for her, on multiple days throughout the weeks put the baby on her and do what he called circumstantial acting. We filmed take after take to see whether the baby does something that unintentionally looks like it’s a choice. This was done until we had enough randomness and good performances come out of that. That was fun from the get-go.” The performances did not vary all that much with the stand-in babies. Cramer says, “As long as the baby is not looking into the camera and appearing as a baby, you’re good! We matched the different babies’ performances that weren’t on set, in the right situation, except for a few priority shots where we would pick from a library of performances of the real baby similar to a HMC [Head-Mounted Camera] select, which we’d match and animate.”

Johnny Storm as the Human Torch was originally developed by Digital Domain. “We mainly did the bigger flying shots, so luckily, we didn’t have to deal so much with his face while performing,” Cramer remarks. “It was principally body shots. A number of times the face was kept clear, which helped a lot.” LED vests were on set to provide interactive lighting on the face. “The core idea was that oxygen is leaking out of his skin, so there would be this hint of blue flame that catches and turns into the red flame. The hope was to have that together with these leaking flames so it feels like its emanating from inside of him rather than being just on the surface. We did not do some of these dialogue shots when he’s on fire. They used different techniques for that.” The initial idea was to have the hands and feet ignite first. Cramer notes, “We also played with ideas where it [a flame] came from the chest; having some off-set helped a lot. They trigger initially and have a big flame rippling up fast. I found it wasn’t as much of a challenge. The hardest thing with the look was how he appears when fully engaged in flames – what does his face turn into? He would have this strong underlying core that had a deep lava quality. We were not the driver of this. There were other vendors who took over the development and finished it.”

Element shoots were conducted on set. “What happened with Scott [Stokdyk, Visual Effects Supervisor] early on was we filmed a bunch of fire tests on set with different flames and chemicals to get various colors and behaviours,” Cramer explains. “They would have different wind speeds running at it. That became the base of understanding what fire they wanted. Our biggest scene with that was when they’re inside the Baxter Building and [Human Torch] has a dialogue with Mr. Fantastic [Pedro Pascal]. The flames there are realistic. Our goal was to have a gassy fire.” Tests were done with the stunt performers for the flying shots. ”The stunt performers were pulled on wires for the different flying options, which became the initial starting point. We would take those shots, and work with that. We played with ideas such as hovering based on the subtleties of hand thrusters that Johnny can use to balance, but the main thrust comes from his feet.”

Simplicity was key for effects, such as invisibility for the character of Sue Storm. “The whole film is meant to feel like older effects that are part of the period,” Cramer states. “We tried having a glass body and all sorts of refractions through her body. In the end, we went relatively simple. We did some of the refraction, but it was mainly a 2D approach for her going fully invisible in the shots. We did subtle distortion on the inside edges and the client shot with different flares that looked nice; this is where the idea of the splitting camera came from, of showing this RGB effect; she is pulling the different colors apart, and that became part of her energy and force field. Whenever she does anything, you normally see some sort of RGB flare going by her. It’s grounded in some form. Because of doing the baby, we did this scanning inside where there’s an x-ray of her belly at one point. Those shots were fascinating to do. It was a partial invisibility of the body to do medical things. We tried to use the flares to help integrate it, and we always had the same base ideas that it’s outlining something that hums a little bit. We would take edges and separate them out to get a RGB look. For us, it started appearing more retro as an effect. It worked quite well. That became a language, and all of the vendors had a similar look running for this character, which was awesome.”

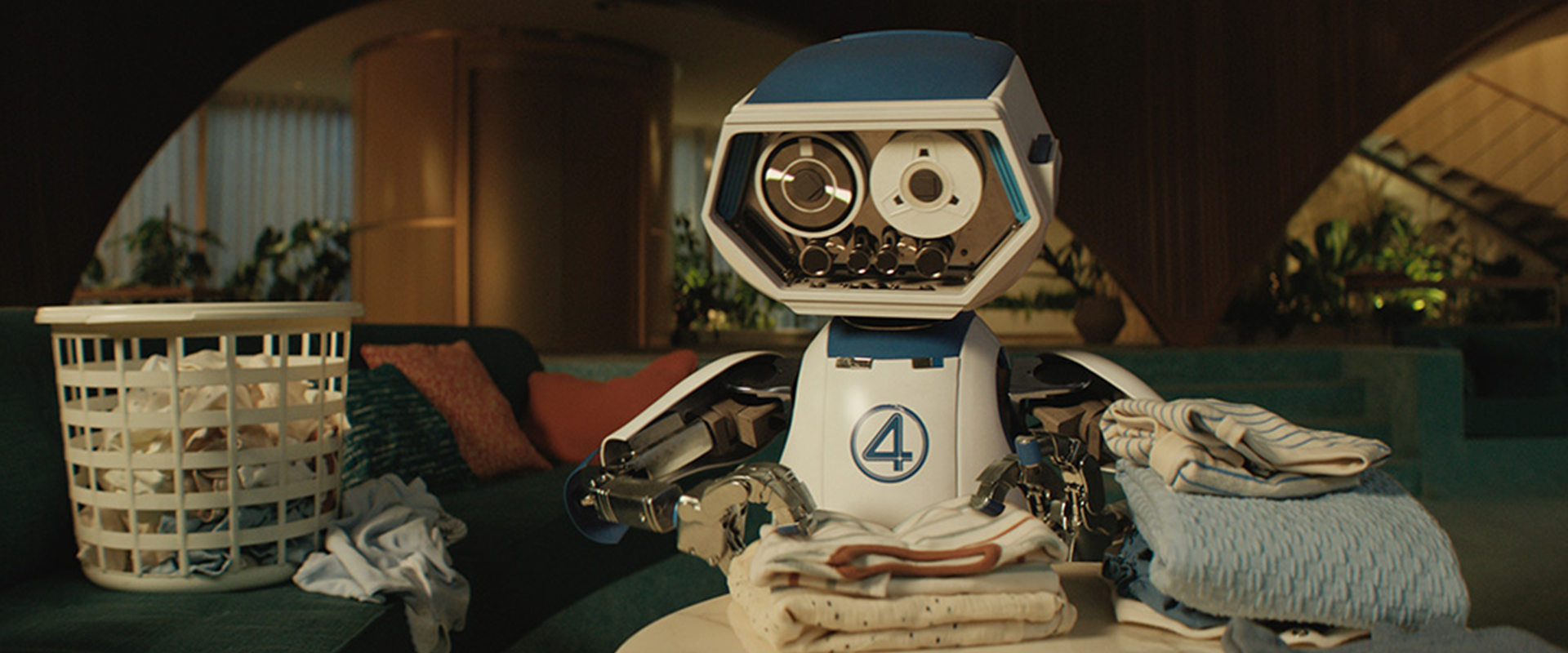

Assisting the Fantastic Four is a robotic character known as H.E.R.B.I.E.(Humanoid Experimental Robot-B Type Integrated Electronics), originally conceived for the animated series. “Right now, there is this search to ground things in reality,” Cramer observes. “There was an on-set puppeteered robot that helped a great deal. There is one shot where we used that one-to-one; in all the others, it’s a CG takeover, but we were always able to use the performance cues from that. We got to design that character together with Marvel Studios from the get-go, and we did the majority of his shots, like when he baby-proofs the whole building. We worked out how he would hover and how his arms could move. We were always thinking how H.E.R.B.I.E. is meant to look not too magical, but that he could actually exist.” The eyes consist of a tape machine. Cramer observes, “We had different performance bits that were saved for the animators, and those were recycled in different shots. It was mainly with his eye rotation. He was so expressive with his little body motions. It was more like pantomime animation with him. It was obvious when he was happy or sad. There isn’t so much nuance with him; it’s nice to have a character who is direct. It was fun for the animators and me because if the animation works then you know the shot is going to be finished.”

The overarching breakthrough on this show for Digital Domain was providing other vendors with facial data. “To funnel it all through us and then go to everybody helped a lot. It was something different for us to do as a vendor,” Cramer states. “That’s something I’m proud of.” The ability to share with other vendors will have ramifications for Masquerade 3. “That should be a general move forward, especially with how the industry has changed over the years. Everybody has proprietary stuff, but normally now we share everything. You go on a Marvel Studios show and know you’re going to get and give characters to other vendors. In the past, you would have Thanos, and it would be Wētā FX and us. But now four or five vendors work on that, so you have five times the inconsistencies getting introduced by having different interpretations of their various systems. It is helpful to funnel it early on and assemble scenes, then hand it out to everybody. It speeds up everybody and gets the same level of look.”